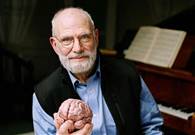

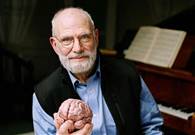

I was saddened yesterday to learn that Oliver Sacks had succumbed to the cancer that he announced last February. He was 82 years young.

Sacks researched and wrote about various brain anomalies, one of which was Tourette’s syndrome. It made me recall some experiences I’ve had.

I was an LA County Beach Lifeguard from 1965-2000 and had many great experiences during that long period. One of them had to do with a lifeguard colleague on Venice Beach who was looking for a place to rent. I suggested an upstairs apartment in Santa Monica, a four-plex on 3rd st. where I once lived. He moved in and the trouble started right away. A good friend of mine since high school, living in the unit below, was going to law school and needed to study all the time. My lifeguard friend would scream out expletives at 2, 3, or 4 in the morning. Finally my downstairs friend went up the stairs and confronted him with a baseball bat, thinking these outbursts were willful. The lifeguard had Tourette’s. This was in the early 1970s, when most people didn’t know about Oliver Sacks writings on the neurological syndrome.

Much later, teaching a music salon in my former home in Venice, there was a sweet guy named Christopher who’d always sit upstairs. Problem was that he would occasionally produce a loud salvo of profane words from his upstairs perch. This was in the early 1990’s. After a while, it just didn’t bother us. Later I realized he had Tourette’s too.

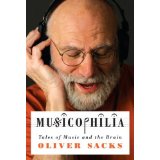

Thanks to Oliver Sacks I and others know much more about Tourette’s than I used to. I also appreciate his love of music, which he expresses so movingly in his book Musicophilia. I, like him, am a musicophile, a mélomane, as it’s called in French. He loved the music of Mozart and was a superb pianist who could do justice to it. He wrote about musicophiles like himself and the opposite extreme, people with amusia for whom Mozart sounded like pots and pans falling on the floor. He also wrote in Musicophilia about people who understood music very well, using classical musicians as an example, but who found no beauty or anything emotional in music.

His studies on alzheimer’s patients also showed us the power of music on older people frozen in time. In this video (Oliver Sacks is commenting on it) we see Henry, catatonic, come to life with his rediscovery of music He is so far gone he doesn’t recognize his own daughter, yet music brings him back to life.

http://blogs.kcrw.com/rhythmplanet/alive-inside-more-proof-of-the-power-of-music/

I loved Michiko Kakutani’s eloquent piece on him in today’s New York Times.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/31/arts/oliver-sacks-wrote-awakenings-and-cast-light-on-the-interconnectedness-of-life.html?em_pos=large&emc=edit_nn_20150831&nl=nytnow&nlid=71902421

I’m near Chris Burden’s age, so some of my life story aligns with his. One of those intersections was the Vietnam War, or The American War, as it’s known in Vietnam and some other places. I never wanted to serve in Vietnam, and moved to Paris to go to school and took my Army physical in Germany. In Los Angeles you would be inducted no matter what. There was a big quota to fill. I had high school chums who got killed there, and other friends who returned psychologically damaged. As we know now, it was a trumped up war, as McNamara admitted later on; we should have learned from the French debacle but didn’t.

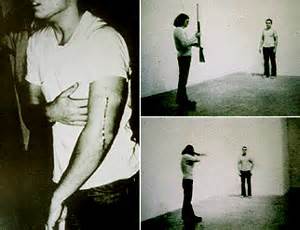

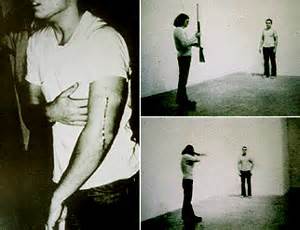

Burden, who died yesterday at 69 of melanoma, lived in Los Angeles, had a studio in Topanga Canyon, and taught at UCLA, my alma mater. Although he is best known for his extreme conceptual / performance piece, Shoot (1971), a personal reaction to the Vietnam War and all the people being shot and killed there, and many of his shows in various LA galleries, the piece I most remember was at the Museum of Modern Art in 1992: It was called The Other Vietnam Memorial, a counterpoint to Maya Lin’s huge Washington D.C. Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

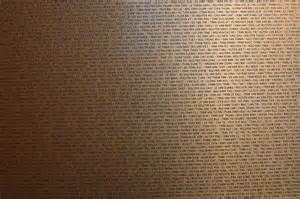

It was an immense series of revolving copper plates, 13′ tall, and filled with etched names of the three million war dead, including the 57,939 American fatalities and the more than two and a half million Vietnamese dead, both military and civilian. He gathered the names from Vietnames phone books. You would move the huge heavy sheets around like you would in a poster shop with large posters. It is one thing to think 3 million people; it is another thing to behold and digest just how many human beings those names represent.

It was powerful and truth be told I just fell apart in the museum that day. Seeing the enormity such loss was devastating.

Today we look toward Normandy for the 70th anniversary of that amazing June 6, 1944 invasion that cost many American lives. It will probably be the survivors’ last get-together.

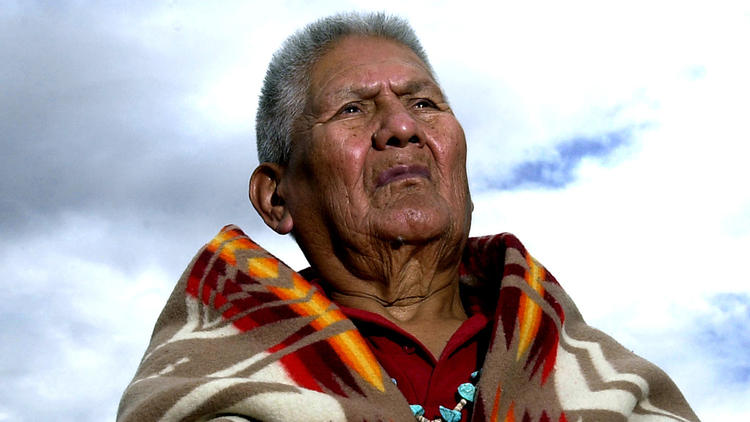

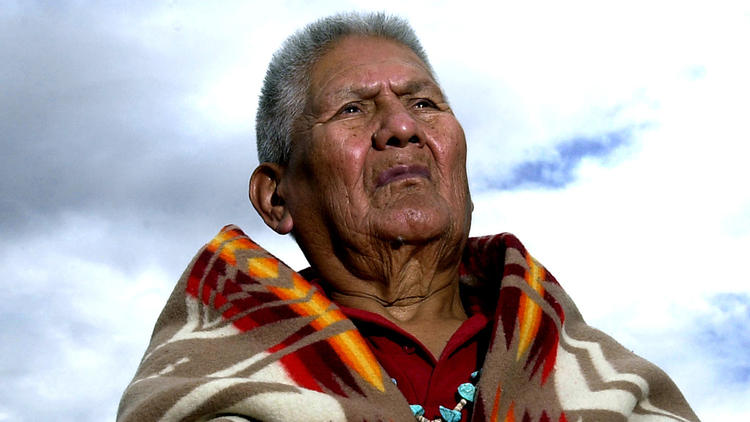

But let’s not forget other battles on the other side of the world. The final Navajo warrior just passed away. His name was Chester Nez. He was 93.

The idea of using the Navajo language to stump the Japanese was a brilliant one. It came from a WWI veteran who grew up near a Navajo reservation. The Marines showed up at his Tuba City, Arizona high school and recruited him along with other Navajo students. After training they were shipped out and covered some of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific Theater: Bougainville, New Guinea, Guam, Peleliu, Iwo Jima.

The Marines were a far cry from what Nez grew up with: if you spoke Navajo in school, you’d get punished and your mouth washed out with soap. Nez’ father insisted that the young boy also learn English so as to get ahead in life.

Even though discriminated against, the code talkers felt a responsibility to aid America. Upon returning after the war, however, they had a hard time finding jobs because they were sworn to secrecy about their work backgrounds. And racial discrimination continued against them. Chester was able to find work as a maintenance worker at a VA hospital in Albuquerque. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President George W. Bush in 2001. His memoir, Code Talker, was published in 2011.

The British were brilliant in dropping aluminum foil into the skies foiling German radar during the war. But I think the idea to use Navajo code talkers was even more brilliant. May Chester Nez be blessed in the afterlife.

Here is the LA Times obit by Elaine Woo:

http://www.latimes.com/nation/nationnow/la-na-nn-last-navajo-code-talkers-has-died-20140604-story.html

(In the photo gallery above, we see Onoda as a young soldier, a photo of him the day he was brought off Lubang island; making up for lost time while dancing with a Playboy bunny, surrendering his sword to President Ferdinand Marcos, and his cattle ranch near Sao Paulo, Brazil).

I just read Hiroo Onada’s obit; it was in both the LA and NY Times today. He was a soldier of rare determination and devotion to duty and to the Emperor. He lived on a Philippine island for 29 years, from 1945 to 1974, following his final orders to stay and fight as the Americans were launching their final surge onto Japan. He was officially declared dead in1959.

I remember reading the newspaper article all the way back in March, 1974, when he was found on Lubang Island in the Philippines, about 90 miles from Manila. I was amazed then, and amazed again now.

At first he wouldn’t leave because he thought, even after almost three decades living in the jungle, that the war was still going on and he had received no further orders than the one to stay and fight from 1945. There were searches for him, leaflets dropped from American planes saying the war was over, but he didn’t believe it. It took a visit from his commanding officer who had given him his marching orders to convince him that the war was over and Japan had surrendered. The Imperial army followed a code that said death was always preferable to surrender. Onoda was 52 when he was discovered.

Before returning to Japan, he went to Manila and surrendered his sword to then-President Ferdinand Marcos. He wore his now 30 year old imperial army uniform and cap during the ceremony; his uniform was in remarkably good condition.

For a soldier who believed in the Emperor’s divinity and who thought the war was a sacred cause for the Emperor, it was not easy to return to a new Japan unrecognizable from the one he left so long before. He felt himself to be a stranger among all the new shiny buildings and cars and modern amenities unheard of in the 1940s. Nevertheless, he got a hero’s welcome when he finally returned.

He hurried to establish a new life, married, and moved to Brazil where he became a cattle rancher. He still made trips back to Japan. He said he needed to hurry and catch up after so many years hiding in the jungle, living off coconuts, bananas and whatever rice he could steal. He also killed villagers’ cows in order to make beef jerky.

On February 20, 1974, a young traveler named Norio Suzuki went to Lubang island with the express purpose of finding the missing soldier. He set up a tent and stayed in the jungle until Onoda finally emerged from hiding. It was after this that Onoda’s commanding office, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi, was called on to fly to Lubang to convince Onoda that the war was over and that he could return to Japan.

There was a book and a movie based on his life in hiding and his return to modern life.

Here is a part of the movie from youtube. I think they’re speaking in Tagalog. This is part one. There are 4 parts.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=scByzMHo0Q4